The Cross in Early Christian Art

There are no realistic representations of Christ Crucified and his passion in early Christian Art. Realistic portrayals of Christ on the cross and his passion only appear in the early middle ages in the western church. The Crucifixion of Jesus was only portrayed symbolically at first, as in the example above, and early on appears in a variety of ways.

The Anchor Cross

Travelers from one port to another on the Mediterranean Sea at the time of Jesus were never sure of a safe passage until they dropped anchor. The anchor became the symbol of safe arrival, and so ancient seaports on the Mediterranean like Alexandria and Antioch adopted the anchor as a symbol for their city.

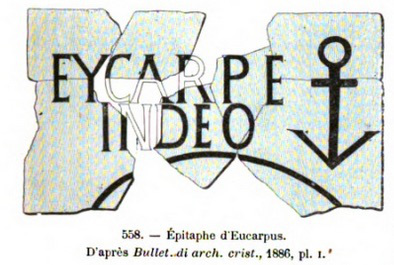

Early Christians used the anchor as a symbol of their hope of reaching a heavenly port, the kingdom of God; they inscribed it on their burial sites in the catacombs to express their hope in Jesus Christ. The anchor closely resembles a cross and early Christians surely saw its resemblance. It’s the most common and sometimes only mark found on the earliest Christian graves in the ancient Roman catacombs of Priscilla, Domitilla and Callistus.

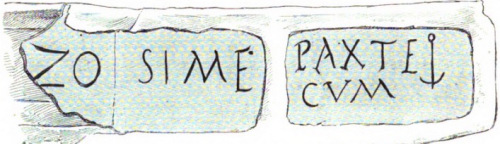

“Pax tecum,” “Peace be with you” the inscription (above) next to an anchor on one of these grave sites reads; the name of the deceased has been half-destroyed by grave robbers looking for valuables long ago. “Eucarpus is with God” we see in another below.

One reason early Christians hesitated to portray the crucifixion of Christ realistically was because the practice was still common in the Roman world until the Emperor Constantine banned it in the 4th century. With crucifixion still before their eyes, Christians would hardly want it portrayed realistically in art, even if it were the crucifixion of the Savior.

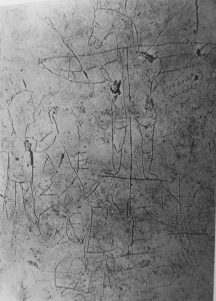

The oldest known portrayal of the crucifixion of Jesus, (left), is a mocking graffiti found on the wall of a barracks on the Palatine Hill in Rome, showing a crucified man with the head of a donkey, and before him a man with hand raised to the image. The Greek inscription from about the year 220 AD reads: “Alexander worships his god.” Undoubtedly, an instance of a Christian being mocked for belief in Jesus crucified.

The first centuries of Christianity, in fact, produced little art. For one thing, it inherited a strong iconoclastic tradition from Judaism. The 2nd century writer Justin Martyr also offers another explanation in his Apology disputing Roman claims that Christians were atheists and a danger to society. Justin acknowledges they had no temples, no statues of gods, and did not participate in the rites of prayer as other Romans did. But Christians were loyal Romans who believed in God, Justin argues. They worship, though, in their own homes and pray there to a God who cannot be imagined or adequately portrayed. (Apology 9,67)

Great Christian churches and shrines were not built till the 4th century, after emancipation by the Emperor Constantine. Before that, Christian art is found mainly in the catacombs, where Christians buried their dead.

The art of the catacombs, which are located mostly around the city of Rome, comes down to us in a fragile state and can be hard to decipher after being underground for centuries. Its simple symbolic style can leave its powerful religious significance unappreciated. Art historians lament its lack of style compared to the sophisticated Roman art of its day.

The writings of Justin Martyr and other early Christian writers may help us better understand its simple, powerful message. In his Dialogue with Trypho the Jew, Justin uses a list of Jewish scriptures that he claims predict the coming of Christ, his life, death and resurrection. The core of these scriptures, commonly used by other Christian writers of his day–Tertullian, Barnabas, Irenaeus– were already used in the preaching message of the New Testament to prove that “all the prophets bear witness” to Christ, the promised Messiah. (Acts 10,43) Jesus, of course, was the first to appeal to Moses and all the prophets to show why it was necessary for the Messiah to suffer. (Luke 24,26-27)

These same Jewish scriptures influenced the formation of the gospels. Other references were added in time and became part of early Christian baptismal catechesis, Christian worship and decoration for the Christian resting places of the dead. The Jewish scriptures are the key to understanding the art of the catacombs.

In his Dialogue with Trypho Justin proposes to his Jewish opponent scriptures such as Psalm 22 and the Servant Songs of Isaiah 53, that indicate God’s plan to send a suffering Messiah who would redeem his people. These same scriptures shaped the accounts of the passion of Jesus in the four gospels.

In his Dialogue with Trypho Justin proposes to his Jewish opponent scriptures such as Psalm 22 and the Servant Songs of Isaiah 53, that indicate God’s plan to send a suffering Messiah who would redeem his people. These same scriptures shaped the accounts of the passion of Jesus in the four gospels.

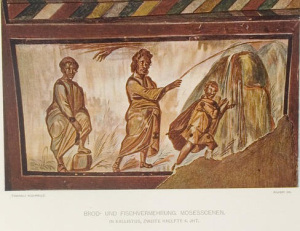

In the 86th chapter of his Dialogue with Trypho, Justin lists other scriptures, beginning with the tree of life planted in paradise, that reveal the saving power of the wood of the cross. That saving wood was prefigured in the wooden rod Moses used to bring water from the rock in the desert and divide the sea for his people to pass over. The cross was prefigured in the ladder Jacob saw mounting to heaven. Abraham saw it in the oak at Mamre and in the wood Isaac carried to his sacrifice. David saw the cross in the tree planted by running waters, mentioned in Psalm 1. The cross was signified in the wood that saved Noah from the flood.

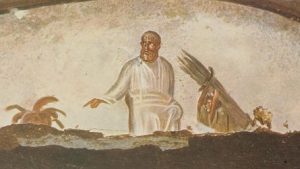

Many of these Old Testament figures connect wood with water and feature in the early church’s catechesis and rites of initiation. The same catechesis speaks to the dead resting in the catacombs, who believed in Christ. Through baptism and the sacraments Jesus Christ would bring them, through the mystery of his death and resurrection, to eternal life.

In other parts of the Dialogue, Justin offers the Three Children in the Fiery Furnace, Daniel in the Lion’s Den, and other Old Testament stories as images that speak of the Passion of Jesus. All these “signs” also appear extensively in the art of the catacombs.

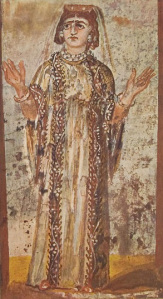

In the 55th chapter of his Apology Justin adds signs from nature and human society to expand his argument for Christianity and the mystery of the cross, A ship can’t sail and arrive at its destination without a sail; a field can’t be plowed without a plow. Both of these are in the form of a cross. Human beings themselves are made in the form of a cross, Justin emphasizes. Figures with arms outstretched, Orants, appear everywhere in the catacombs. They imitate Christ who prayed with arms outstretched on the cross, and his prayer was heard. (Tertullian, On Prayer 14)

The Art of the Catacombs

The art of the catacombs found mostly in the 40 or so catacombs around Rome, offers a rich fascinating look at early Christian belief. Today in the Catholic Church’s prayers for the dying we can still hear the figures portrayed there invoked once more.

“Welcome your servant, Lord, into the place of salvation…Deliver your servant Lord, as you delivered Noah from the flood, Deliver your servant, Lord, as your delivered Moses from the hand of Pharaoh. Deliver your servant, Lord, as you delivered Daniel from the lion’s den.

Deliver your servant, Lord, as you delivered the three young men from the fiery furnace. Deliver your servant, Lord, as you delivered Job from his sufferings. Deliver your servant, Lord, through Jesus our Savior, who suffered death for us and gave us eternal life.” (Roman Ritual)