Fr. Robin Ryan CP

A Review of the Writings of Fr. Robin Ryan CP

by Fr. Martin Coffey, CP

THE MYSTERY OF HUMAN SUFFERING

Robin Ryan’s book, God and the Mystery of Human Suffering[1]

was published in 2011. It is no surprise that Robin would explore the mystery of suffering since he belongs to the Congregation of the Passion whose mission is to ponder the mystery of Jesus’s suffering and how it is related to the suffering of people. Robin’s book does not aim at providing a Christian explanation or justification of suffering. No such thing is possible. He wants rather to search the scriptures and the long tradition of Christian reflection for some helps in responding pastorally to people who are suffering. Throughout the ages many thoughtful and saintly people have raised serious questions about the Christian belief in a good and omnipotent God who seems to do nothing in the face of monstrous suffering. Christians feel compelled to respond to these searching and challenging questions by trying to make sense of their faith in a benevolent God in the face of the stark reality of evil and terrible human suffering. Can we still believe in a good and omnipotent God who apparently allowed the holocaust or Shoah? Robin Ryan’s book belongs to this tradition of serious and unquiet questioning of God.

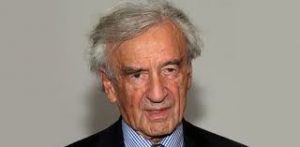

There has been so much suffering in the history of the world but maybe none so calculated and evil as the suffering inflicted on the Jewish people by the Nazi regime. Contemporary theological thinking about suffering has been greatly influenced by the horrors of two world wars and especially the Jewish experience of the Shoah. Ryan’s reflections are enriched by his pondering on the writings of Elie Wiesel, a Jewish survivor of the Shoah. Wiesel saw many of his family , friends and neighbors die in the Nazi extermination camps. He remained a man of strong belief in God but he had to struggle with the fact that God remained silent and allowed these horrors to happen. He felt great anger and bewilderment that God could allow his chosen people to go through such a hell of mindless suffering and death precisely because they were God’s people. He cried out in anguish and dismay. He questioned the justice of God. He imagined dragging God before the courts to answer the charges he was bringing against him of indifference, neglect and silence in the face of evil.

To the end of his days, Elie Wiesel wrestled with these questions and this pain but never ceased to believe and to cry out in anguished prayer to God. He could never accept that there was any possible reason or justification for such horrors. The only thing he could do was bring his anguish and dismay to the God he still believed in and join his prayers to the countless laments of Jewish people throughout the ages.

Two other survivors of Nazism are considered here, the protestant theologians Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Jurgen Moltmann. How can a Christian believer respond to the overwhelming reality of human suffering? And how can she reconcile this abiding cloud overshadowing human life with her belief in a good and omnipotent creator God? The many questions directed at the believer from critics and unbelievers suggest that her faith may be misplaced or irrational. There is a glaring contradiction between her naïve belief in a good God and the evidence of experience. Is the creator God responsible for suffering too? Or does God send suffering as a punishment or as a test? Throughout this book the many Christian witnesses insist that God does not want people to suffer. God is not the author of suffering but God responds to suffering by healing the sick and resisting the forces that threaten and diminish human life in any way.

Two other survivors of Nazism are considered here, the protestant theologians Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Jurgen Moltmann. How can a Christian believer respond to the overwhelming reality of human suffering? And how can she reconcile this abiding cloud overshadowing human life with her belief in a good and omnipotent creator God? The many questions directed at the believer from critics and unbelievers suggest that her faith may be misplaced or irrational. There is a glaring contradiction between her naïve belief in a good God and the evidence of experience. Is the creator God responsible for suffering too? Or does God send suffering as a punishment or as a test? Throughout this book the many Christian witnesses insist that God does not want people to suffer. God is not the author of suffering but God responds to suffering by healing the sick and resisting the forces that threaten and diminish human life in any way.

If suffering does not come from God and God does not want suffering, how does it happen and from where does suffering come? This was a great puzzle to Christian thinkers from the beginning. St. Augustine was the one who developed most fully the idea of original sin and how it gives rise to suffering and death. Julian of Norwich had a similar insight into suffering and its relation to sin as its ultimate origin. It is not that a person’s suffering is a direct result of that person’s own particular sins. It is rather that original sin has introduced disorder and chaos into creation and especially into the human being so that now our every thought, desire and action is somehow affected negatively.

This gives rise to the history of sin and the consequent history of great human suffering. Pope Benedict XVI said in Spe Salvi that the suffering that is part of human existence “stems partly from our finitude and partly from the mass of sin that has accumulated over the course of history.” Does original sin also account for the suffering caused by sickness and disease and the consequences of natural disasters? Here once again human thinking has reached a limit and must acknowledge the awful mystery of inexplicable suffering and disaster.

If God does not want us to suffer, why does God allow it? Much ink has been spilled in discussing this problem. Time and again theologians are forced to re-echo the words of Job in the First Testament and of St. Paul who wrote, “Who knows the mind of the Lord? Who has been his counselor?” (Rom. 11, 34). Some theologians (Moltmann, Schillebeecks, Elizabeth Johnson) have spoken about the divine kenosis and suggest that God, in creating the universe, chose to limited Godself. God created the human being with the capacity to choose freely and likewise gave all created things the ability to act according to their nature and the natural laws of evolution. God does not intervene randomly to redirect or reshape creation but freely accepts to abide within these freely chosen limits on Godself. This shows God’s great respect for the integrity of creation and of human beings in particular. To act otherwise would be to dominate, devalue and destroy creation, including the freedom of humans. Therefore, when suffering and catastrophe result from the free action of created things God does not intervene to prevent it. God does not will things to go wrong but time and again has shown a readiness to help us and to rescue us. This is the story of God’s dealings with the people of Israel in the First Testament, especially the story of the Exodus, and then in the New Testament when God sent Jesus to save us.

But God’s self-limiting does not rob God of divine power. God is always the omnipotent one but God’s power is not the sovereign imperial power, like that exercised by human tyrants and others. It is not at all the same as human power or as human’s think God’s power should be. God’s power is not imposition and force. God does not want to dominate creation by power. God’s power is demonstrated throughout the scriptures and especially in Jesus as the power of self-sacrificing love. God has no need of us but freely chooses to create us and to love us ever after. This love is shown in compassion for our weakness and our suffering. We cannot fully explain this but we see it time and time again in the story of Israel and in the life and ministry of Jesus.

Does God care about our suffering? If God is perfect and impassible, as classical theology teaches, can God be moved by our suffering and our prayers for help? Classical theology has insisted on the transcendence and freedom of God. God is not a creature like us and does not react to suffering the way creatures react. God is not afraid of the unknown. God does not lament the loss of anything the way we do. God is not affected by the things that cause us suffering and distress. Does this mean that God is always the impassible One, the great unmoved and unmovable one? The God revealed in the scriptures is one who is close to the people, a God who sees their suffering and intervenes to set them free from slavery and delivers them from their enemies. God does not suffer like us but God chooses to suffer with the people. God walks with them on the arduous ways of their history. God chose to care for this special people and through them and because of them to care for all people. God does not suffer like his creatures but God has chosen to suffer with the people. In the words of St. Bernard Impassibilis est Deus sed non incompassibilis.

Does God care about our suffering? If God is perfect and impassible, as classical theology teaches, can God be moved by our suffering and our prayers for help? Classical theology has insisted on the transcendence and freedom of God. God is not a creature like us and does not react to suffering the way creatures react. God is not afraid of the unknown. God does not lament the loss of anything the way we do. God is not affected by the things that cause us suffering and distress. Does this mean that God is always the impassible One, the great unmoved and unmovable one? The God revealed in the scriptures is one who is close to the people, a God who sees their suffering and intervenes to set them free from slavery and delivers them from their enemies. God does not suffer like us but God chooses to suffer with the people. God walks with them on the arduous ways of their history. God chose to care for this special people and through them and because of them to care for all people. God does not suffer like his creatures but God has chosen to suffer with the people. In the words of St. Bernard Impassibilis est Deus sed non incompassibilis.

Where does the passion of Jesus fit into this? The crucified Jesus seems to be just one more innocent victim of mindless hatred and suffering. How can this be a source of consolation or meaning for suffering people? Does God not also succumb to the relentless force of evil and suffering? Are we not left entirely bereft of all help or rescue?

Christians believe that in Jesus, the Son of God, God really entered into our situation and freely chose to live our life and endure our struggles and suffering. Jesus showed real compassion and care for suffering people and cured many. He responded to hungry people by providing bread, he comforted widows and wept at the death of his friend. Jesus acted to free people from the burdens of suffering. He also had great anxiety in the face of suffering showing that he appreciated the horror of it. There is nothing in the life of Jesus that suggests that God treats suffering lightly. Everything points to the truth that God is always close to us and acts on our behalf against all that diminishes our life and causes us suffering.

Christians believe that in Jesus, the Son of God, God really entered into our situation and freely chose to live our life and endure our struggles and suffering. Jesus showed real compassion and care for suffering people and cured many. He responded to hungry people by providing bread, he comforted widows and wept at the death of his friend. Jesus acted to free people from the burdens of suffering. He also had great anxiety in the face of suffering showing that he appreciated the horror of it. There is nothing in the life of Jesus that suggests that God treats suffering lightly. Everything points to the truth that God is always close to us and acts on our behalf against all that diminishes our life and causes us suffering.

Fr. Martin Coffey, CP

JESUS AND SALVATION

Robin Ryan was inspired to write Jesus & Salvation[2] on the Christian understanding of salvation in response to an experience he had in Haiti in the summer of 2012.

Robin Ryan was inspired to write Jesus & Salvation[2] on the Christian understanding of salvation in response to an experience he had in Haiti in the summer of 2012.

There he witnessed the devastation and the misery of a people accustomed to unbelievable suffering. One particular little girl made a deep impression on him and he wondered what the message of salvation could possibly mean in her life. This book therefore has an urgent pastoral intent. It wants to bring the message of salvation into contact with the reality of human suffering and anguish. A merely intellectual grasp of the meaning of salvation is not sufficient. Something more is needed. This is what lies behind this wide ranging and rich overview of the very best in Christian reflection on the proclamation of salvation in Jesus Christ.

Fr. Ryan adopts a chronological approach to his treatment of salvation. In this way we are presented with the most compelling biblical, patristic, medieval and modern ways of presenting salvation. This is a huge sweep through millennia of thinking, writing and praying on the central mystery of the Christian faith in Christ as the savior of the world. We discover early on in this study that there cannot be any one final definition of salvation. The idea of salvation is rich and analogical. It is nourished on many biblical and other images and metaphors. It attempts to capture and express the unfathomable mystery of God and God’s loving care for a sinful and suffering people.

We Christians profess that Jesus died to save us but we are not always very clear about what he is saving us from or what difference this salvation makes in our daily life. At the end of this study we know why it is not possible to give a simple one dimensional definition of salvation. We also appreciate just how wide and deep is God’s saving love and how it penetrates every dimension of our existence, healing and transforming not only us but the whole creation. I think one of Robin’s objectives in writing this book was to free us from the anxious intellectual questions and abstract speculations about the nature of salvation and instead tries to convince the reader that God’s creative and saving love is being poured out over us continually and this becomes a motive for our praise and an endless source of delight.

Robin treats of all the classical ways of understanding how salvation was won for us. The early Church emphasized the salvific nature of the incarnation whereby Christ became poor in order that we might become rich or as many early teachers put it, he shared our human life so that we could share his divine life. Salvation is this wonderful exchange and is the cause of the new life Christians share with the risen Christ. This way of seeing salvation remains the most important for Orthodox Christians.

Western theology and spirituality has been greatly influenced by the thinking of St. Augustine who focused on the salvation of the individual sinner. Because of his dispute with the Pelagians, Augustine emphasized the sinful nature of every human being and the need to be saved by the grace of God. This focus on individual salvation has become the fixed preoccupation of Christian reflection ever since. Even new born babies need to be saved from the damning effects of original sin. Augustine insisted on human responsibility for rejecting God’s plan. This is in keeping with human dignity and human freedom. (It has always baffled me how this Augustinian line of argument insists that human freedom is powerful enough to reject God but the same human freedom is totally incapable, without the assistance of grace, of choosing God and doing good. This is the material for another book.) The biblical idea of salvation usually had the people in view and not the individual. Salvation meant a new way of life for the whole people who would at last experience the just rule of God and delight in God’s gift of Shalom or peace.

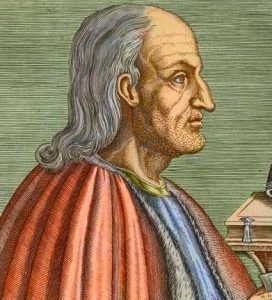

The most famous attempt to understand salvation is found in St. Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109). Anselm belonged to a new generation of Christian thinkers who valued reason and logic very much and he applied these to the question of salvation. He asked why did God become man in Christ and he answered that the Son of God became man to save us by taking our place in paying the price of our salvation. Robin Ryan helps us to appreciate Anselm’s difficult theology by setting it in the context of contemporary theological disputes with Jewish thinkers who considered the Christian doctrine of the incarnation and the crucifixion of the Son of God as derogatory to the dignity and impassibility of God. Anselm wanted to display the perfect logic and intelligibility of Christian faith. His aim is to convince his readers that it was fitting for God to act in this way.

The most famous attempt to understand salvation is found in St. Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109). Anselm belonged to a new generation of Christian thinkers who valued reason and logic very much and he applied these to the question of salvation. He asked why did God become man in Christ and he answered that the Son of God became man to save us by taking our place in paying the price of our salvation. Robin Ryan helps us to appreciate Anselm’s difficult theology by setting it in the context of contemporary theological disputes with Jewish thinkers who considered the Christian doctrine of the incarnation and the crucifixion of the Son of God as derogatory to the dignity and impassibility of God. Anselm wanted to display the perfect logic and intelligibility of Christian faith. His aim is to convince his readers that it was fitting for God to act in this way.

Anselm paints a picture of God as the supremely good creator whose creatures, by sinning, have dishonored God and spoiled the beauty and order of creation. Salvation means the restoration of order and the just punishment of those who dishonored God. The demands of justice must be satisfied. It is not a matter of appeasing an angry God. God’s well ordered creation has been damaged and God has been dishonored. The key idea at work here is justice or the restoration of right order. God is supremely good and just. Justice requires restoration of order and of God’s honor. This requires that the sinner satisfies the demands of justice and accepts just punishment. The human being is incapable of offering appropriate satisfaction. It is beyond his finite capacity. The only possible outcome is the destruction of the sinner. But God is also merciful and does not exact the proper punishment from his sinful creatures but instead sends his Son who alone, because He is also divine, can satisfy the demands of divine justice.

The logic of Anselm’s argument suggested that the great and perfect God is someone who is easily offended by mere finite creatures and who demands an impossible satisfaction. Since finite and limited human beings were unworthy and could not offer sufficient satisfaction to satisfy the wounded honor of God, God decided to send his Son to offer a sufficiently worthy satisfaction. To modern ears this sounds like a very unattractive and easily offended God who is hard to reconcile with the Father revealed by Jesus in the Gospels.

Anselm’s theory of the atonement was greatly appreciated in an age that had rediscovered logic and tight argumentation as tools for penetrating the mysteries of God. The clarity and rigorous nature of Anselm’s argument attracted admiration and was felt to be compelling. Since then the fascination with rigorous logical argument in theological matters has lost its shine. Contemporary theology has become more attentive to the incomprehensibility of God and his mysterious ways. God is always more and greater than anything human logic can discover.

The great medieval theologians, as well as those of the Reformation, continue to reflect on the logic of salvation, why and how it happened. Thomas Aquinas showed his usual moderation in affirming the usefulness of different ways of talking about salvation. While he values Anselm, Aquinas puts more emphasis on Christ’s love as the motive and source of our salvation. Martin Luther had a life-transforming experience of the righteousness of God who freely saves us without need of our works. He was convinced that there is absolutely nothing we sinners can do to earn, merit or attract the merciful salvation of God. Salvation is wholly the free and loving initiative of God. Only God can save us and that was the work of Christ on our behalf. He suffered and died for us and so saved us. Because human beings are so radically disordered by sin, salvation is always beyond our reach and only Jesus can bring it to us and bring us to it.

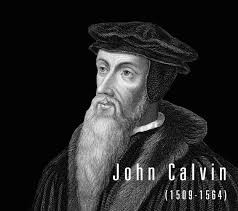

John Calvin shared Luther’s convictions about the free gift of salvation. He developed the idea that Jesus took our place and endured the terrible but just punishment of sin as our substitute. Both reformers have a strong sense of the wrath of God directed against sin. Sin must be taken terribly seriously and in dealing with sin God is forced to go to extreme lengths to deal with it. The full force of God’s wrath could not have been endured by finite human beings. It would have meant eternal death. Only the Son of God could have survived the wrath of God and come through death to a new life in the resurrection.

These very powerful reflections on the nature of salvation have continued to influence millions of Christians in the various Protestant and Reform churches. They encourage a great sense of personal relief for having been spared the terrible wrath of God and also deep gratitude and reverence for Jesus who stood in our place. However, the underside of these ways of thinking about salvation is that God is seen as a demanding and harsh judge who is pleased to see his Son suffering and die to appease him. Some contemporary theologians have no hesitation in saying that this kind of theology leaves us with a monstrous view of God.

Ryan also explores a number of contemporary theologies of salvation. He gives clear and attractive summaries of Karl Rahner, Hans Urs von Balthasar and Edward Schillebeecks. After Vatican Counci II, these were three of the most influential Catholic thinkers. Rahner and Balthasar in particular gave rise to schools of theology that were in some respects complementary and in tension. Ryan greatly appreciates Schillebeecks detailed study of the New Testament references to salvation. In his writings, Schillebeecks lays bare the great variety of images and metaphors used by New Testament writers when talking about the saving work of Jesus. The New Testament does not give us one definitive way for understanding what is meant by salvation. Von Balthasar is a Swiss theologian who has dialogued with Reform theologians for years. I think it is possible to detect the influence of the Reform preference for the theories of blood sacrifice and penal substitution in his theology.

Robin seems to show a liking for Rahner’s approach which emphasizes God’s unchanging saving love for all of his creatures. The work of Jesus does not bring about a change in God but rather makes God’s love visible and effective for us in a new way. He applies the logic of sacramental causality to Jesus’s work of saving us. The sacraments are visible signs that make God’s grace active and effective in us. Jesus birth, life, ministry, suffering, death and resurrection make God’s saving love visible and effective in a new way for the salvation of the world.

I was particularly happy that Robin included powerful reflections on the cosmic dimension of salvation as well as it universal reach. We now see more clearly than ever how human existence is the outcome of an emerging universe and the long intricate process of evolution. In other words, human existence is intrinsically interconnected with the total story of the universe. Fr. Thomas Berry CP was a pioneer in exploring the importance of the story of the universe.

The Christian belief in the resurrection of the body must imply some kind of resurrection of all that goes into the making of the human body and that is the whole 13.7 billion year cosmic process from the so-called Big Bang until the end. Theology has not yet offered a satisfactory theory of how that might happen but at least we are now at last acknowledging the more complex truth of our nature as material beings that are part of a much larger cosmic whole. On the question of universal salvation, Robin presents the case of those who argue for the presence and action of God outside the boundaries of the Church. Vatican II had already opened the door to this kind of exploration in Nostrae Aetatae, the document on the Church’s relationship with non-Christian religions. The council declared that the Catholic church rejects nothing of what is true and holy in other religious traditions. Theologians argue that Jesus is truly the unique savior of all people but that the fruits of salvation can be accessed by non-Christians who sincerely practice what is good in their own religions and by following the dictates of their conscience.

I am grateful to Robin for gathering all this material in an attractive and very readable volume. The many authors he draws on offer us a great variety of ways of accessing the mystery and the beauty of God’s saving actions on our behalf and especially in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. His work is a masterful survey of Christian theology that ends with his own insightful theological reflections.

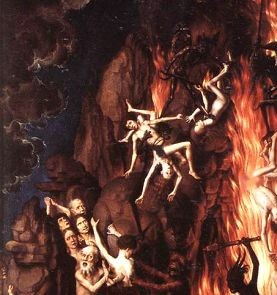

When I begin to think about the possible meanings of being saved, I do not think first of all about the theological speculations of the great teachers of the Church. I am immediately reminded of a little prayer that is said every day by millions of Catholics who recite the daily rosary. After each decade they pray, “O my Jesus, forgive me my sins and save me from the fires of hell . .” It seems to me that the ordinary Catholic is more conscious of the need to be saved from “the fires of hell” than any other kind of salvation. Robin belongs to the Congregation of the Passion whose principal ministry for more than two hundred years was preaching popular missions to the people. A considerable part of the popular mission was devoted to preaching on the Four Last Things – death, judgment, hell and heaven. This kind of popular preaching played a significant part in forming the Catholic imagination. I am thinking of the famous and terrifying sermon on hell in James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Catholics lived in a world overshadowed by the prospect of severe judgment and punishment after death. Fear played a significant role in their life of faith and devotion and, more than that, it cast a dark pall over every aspect of their Catholic lives. I think it may have been influenced by a form of neo-Augustinian pessimism about human nature that was and still is fairly widespread in the Catholic Church.

When I begin to think about the possible meanings of being saved, I do not think first of all about the theological speculations of the great teachers of the Church. I am immediately reminded of a little prayer that is said every day by millions of Catholics who recite the daily rosary. After each decade they pray, “O my Jesus, forgive me my sins and save me from the fires of hell . .” It seems to me that the ordinary Catholic is more conscious of the need to be saved from “the fires of hell” than any other kind of salvation. Robin belongs to the Congregation of the Passion whose principal ministry for more than two hundred years was preaching popular missions to the people. A considerable part of the popular mission was devoted to preaching on the Four Last Things – death, judgment, hell and heaven. This kind of popular preaching played a significant part in forming the Catholic imagination. I am thinking of the famous and terrifying sermon on hell in James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Catholics lived in a world overshadowed by the prospect of severe judgment and punishment after death. Fear played a significant role in their life of faith and devotion and, more than that, it cast a dark pall over every aspect of their Catholic lives. I think it may have been influenced by a form of neo-Augustinian pessimism about human nature that was and still is fairly widespread in the Catholic Church.

I would have liked to see more space devoted to this very dark religious mindset and how it may have distorted people’s view of God and of salvation. I’m sure the imagery and emotional tone generated by this kind of preaching and popular piety persists in many places. It does not help people to open themselves to God and to welcome his generous and undeserved blessings. Before people can appreciate the riches presented in this book, I believe they may first need to be set free from older and more negative ways of seeing salvation.

There is another aspect of salvation that we find in the Song of Zechariah at the beginning of Luke’s gospel. Zechariah is praising God for God’s goodness in remembering the ancient promises and now acting definitively by sending a savior. Zechariah’s prayer says that the savior is one who “frees us from fear and from all who hate us”. On many occasions, Jesus responds to the pain of the disciples and the people in general by saying, “Do not be afraid.” In his words and deeds, Jesus addresses the fear of the people because he knows that so many of the evils affecting people have their origin in fear. Jesus has come to set the people free from the fear that enslaves them and that robs them of peace.

I have already alluded to the pervasive fear of eternal punishment in the fires of hell. But there are many other fears that destroy human life. Fear is often the source of jealousy, rivalry, hatred and violence. So many other evils have their root and source in fear. Fear of suffering and fear of failure make people do terrible things to protect themselves. I think part of the salvation people long for and pray for is the freedom from the fears that cripple and diminish their lives. Jesus is portrayed in the gospels as one who reached into people’s lives to deal with their fears.

Maybe Robin will take up some of these issues in his next book and help preachers avoid the more gross depictions of God and God’s justice. For now, I am delighted to recommend Robin Ryan’s two wonderful books. Each one gives us a rich and attractive account of the very best in Christian theology. Together they will nourish our thinking, praying and action as Christians committed to advancing the Kingdom of God by addressing the challenges of human suffering and the human longing for salvation.

Fr. Martin Coffey, CP

[1] Robin Ryan, God and the Mystery of Human Suffering: A Theological Conversation across the Ages (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2011).

[2] Robin Ryan, Jesus and Salvation, (Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 2015).