Relics of The Passion of Christ

Relics honored by the Catholic Church may be part of the body of a saint or something that has touched them. The wood of the Cross and other objects believed to have touched the body of Christ are among the church’s most treasured relics and figure prominently in Christian spirituality and art.

Relics, Then and Now

Before considering the major relics of Christ’s passion, death and resurrection it may help to consider how relics were seen in the past and how they are seen after the Age of the Enlightenment in the 17th century when scientific thinking in the western world began to put relics, and other aspects of religion as well, under the microscope of science and reason.

Before the Age of the Enlightenment people generally believed in an “enchanted world”, where heaven and earth were close and God was actively engaged in nature and history. That view appears in the psalms. “The heavens declare the glory of God,” (Psalm.18) God is “maker of heaven and earth, the seas and all that is in them.” (Psalm146) Savior as well as creator, “The Lord sets prisoners free; the Lord gives sight to the blind…The Lord protects the stranger, sustains the widow and orphan, but thwarts the way of the wicked.” (Psalm 146) God “dwells in a holy temple” and they are happy who find him there. (Psalm 84) “God “takes delight in his people.” (Psalm.149)”

Jews at the time of Jesus believed in an “enchanted world.” The temple in Jerusalem was the place where God, the maker of all things, dwelt on earth and reached out to heal and teach. Like the Jews, Christians also believed that God was close, not distant, and could be experienced through holy people and concrete signs and holy places. Their belief is evident in the writings of the New Testament.

The pagan world too believed in an “enchanted world.” At Lystra in Asia Minor, the gentile crowd seeing a cripple get up and walk at St.Paul’s word “ cried out in Lycaonian, “The gods have come down to us in human form.” (Acts 14, 11) Luke later says “So extraordinary were the mighty deeds God accomplished at the hands of Paul that when face cloths or aprons that touched his skin were applied to the sick, their diseases left them and the evil spirits came out of them.” (Acts 19, 12)

Over the centuries, Christians believed that, besides the sensible signs of the sacraments, God shows his power through saints and their remains. Yet even in New Testament times it was recognized that human beings may unfortunately use holy things, holy people and their remains for their own profit and advancement. Peter rebuked Simon the Magician (Acts 8, 18-20) and Paul struggled with the charlatans and peddlers abounding in Ephesus, selling their amulets and spells to needy people. (Acts19, 13-40)) Still, down though the centuries holy relics have been honored in the eastern and western Christian churches.

Interest in relics increased in Christianity in the 4th century after the Emperor Constantine embraced the new religion and opened the places where Jesus lived and died and rose again to Christian pilgrims. As Christian pilgrimage flourished, Christians brought various relics home as reminders of their experience; they prized especially relics of the cross.

Rome and Constantinople were major centers besides Jerusalem in promoting devotion to relics. Popes, religious and political leaders utilized them for promoting spiritual and political goals. Relics of the passion, death and resurrection were especially important in these centers.

Some difference appears in the approach of the eastern and western churches to relics. In the eastern church icons have a prominent place in representing the mysteries of Jesus and his saints. In the western church physical relics are more prominent. Churches and shrines honoring relics and holy images multiplied especially in medieval times in Europe; they’re found today wherever Catholic Christians are.

Reaction to Relics

Reaction to holy images and relics occurred over the centuries. In the eastern church the Iconoclastic Controversy was addressed at the Second Council of Nicea in 787. In the western church a major reaction against relics occurred at the Reformation in the 16th century. Early protestant reformers, Wycliff and Hus, considered relics idolatrous; Luther saw them as temptations to avarice; Calvin protested against false relics. Their views are still held in the religious traditions that follow them today.

The Age of Enlightenment in the 16th century introduced tools of modern science for investigating the world we know. Some scholars, influenced by rationalism, questioned the historicity of Jesus and the gospels as well as relics and the practices honoring them. Their critical approach is still found today in many who consider relics as quaint products of a superstitious past.

The Catholic church welcomes genuine scientific research into its tradition of holy people and the relics of their presence, provided it’s done with respect and without philosophic presuppositions of rationalism. People today, believers and unbelievers alike, want to know where relics come from, how have they been used over time and what they mean in our times.

1. Procession with Relics of the Cross Venice 15th Century 2. Monastic Veneration of the Cross c. 14th century 3. Memoire sur les instruments de la Passion. 4. Good Friday veneration of the Cross, Parish of St. Mary, Colts Neck, NJ 2000

The Relics of the Cross

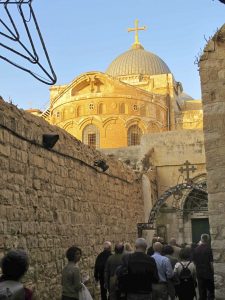

The most prominent relics of the passion, death and resurrection venerated by the Roman Catholic Church were found in Jerusalem in the 4th century by Saint Helena, the mother of the Emperor Constantine, during excavations for the church of the Holy Sepulcher at the traditional site of the crucifixion and burial of Jesus. (cf: http://passionofchrist.us/holy-sepulcher/) (http://passionofchrist.us/the-cross/ )

Witnesses say that St Helena gave parts of wooden crosses from the excavations on Calvary to the church in Jerusalem, the church in Constantinople and to her private chapel in Rome. Fragments from these places became prized gifts sent to other places and individuals in the Roman world.

The relics of the cross placed in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem by Helena were venerated publically at certain times of the year by great crowds, the 4th century pilgrim Egeria reports. Small pieces of the relic were carried by pilgrims to many parts of the world, according to an early bishop of that church, Cyril of Jerusalem. “The whole world is filled with relics of the cross of Christ.”

Confiscated by the Persians during warfare in the 6th century, the Jerusalem relics were retaken shortly afterwards by the Byzantine emperor Heraclitus, but they were seized again during the disastrous battle at Hattin in 1187. The Jerusalem relics then disappeared and were never found; only a small remnant remained, honored today in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem.

Helena’s relics of the cross were also honored in an imperial church in Constantinople; small parts of it were distributed throughout the Roman-Byzantine empire from earliest times. When the city was conquered and sacked during the 4th Crusade in 1204, the relics were among the great prizes taken from the city by western Christian invaders. The confrontation led to bitter relations between the western and eastern churches ever since.

The Roman relics of the cross which Helena placed in her Roman palace are found today in the Basilica of the Holy Cross built on her palace site near Rome’s Lateran Basilica. There are three fragments from the wood of the cross, the wooden sign that refers to the cause of the condemnation, the holy nail, and two thorns from the crown of thorns. The relics have been publicly honored in the Good Friday liturgy at this church since the 6th century, and that service, in turn, influenced the Good Friday liturgy celebrated by Roman Catholics throughout the world.

Relics, Church of the Holy Cross, Rome. Central Panel: Relics of the cross. Top Panel: Relics of the thorns and nails.

Over the centuries, leaders of the Roman church used small pieces of the cross to strengthen faith, forge alliances and unify the church. The 6th century pope, Gregory the Great, gave fragments of Helena’s cross to Recurred 1, King of the Visigoths in Spain, to strengthen his commitment to the Catholic faith. For the same reason, Gregory gave a relic to the son of Teodolinda, Queen of the Lombards. Pope Leo X gave a fragment to King Francis of France in 1515.

Other popes gave fragments of Helena’s relics to shrines throughout the world. Pope Urban VIII placed a fragment near the statue of St. Helena in the newly constructed Vatican Basilica in the 17th century. In 1934, Pope Pius XII gave a fragment of the relic to the sanctuary of Caravaca in Spain to replace an ancient relic stolen in the Spanish Civil War.

Important for spirituality, devotion and diplomacy, Helena’s relics of the cross were protected by religious and secular leaders of the eastern and western church, but they have also suffered damage and neglect over the centuries. Besides incidents already mentioned, relics were stolen for their precious settings or destroyed for their religious associations. The Protestant reformation in the 16th century and the French revolution in the 18th century were notable times of reaction against relics.

One familiar charge against the relics of the cross comes from John Calvin, the Protestant reformer. “If all the pieces of the cross were collected together, they would fill a ship,” Calvin claimed, noting the many suspect relics he saw in his time. A study of existing relics of the cross by Charles Rohault de Fleury in 1870, however, showed that all the known fragments of the cross would only measure a third of what the cross of Jesus would likely be. (Memoire sur les instruments de la Passion)

Besides the relics from Helena’s expedition, the present church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, built over Calvary and the tomb of Jesus and other places in the Holy Land deserve mention. Marking the place where Helena’s relics were found, the ancient church itself is an outstanding relic of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus. Christians pilgrims have flocked to it over the centuries.

Today historians and archaeologists look at it with lively interest as efforts are made to shore up the church’s fragile foundations. From early centuries, pilgrims touched objects to the tomb or the rock of Calvary or the stone considered to be the place where Jesus’ body was anointed and considered them relics of this holy place. Even dirt from the Holy Land became a reminder of the land where Jesus walked and the mysteries that took place there. The practice of seeking sensible reminders of the holy, deeply human as it is, continues even today.

Column of the Scourging

Several places claim to have the Column of the Scourging of Jesus, which was ordered by Pilate after sentencing him to death. (Matthew 28, 27,Mark 14, 65; Luke 22,63-65) The column at St. Praxedes Church in Rome was brought to the city by Cardinal Giovanni Colonna, a leader of the 6th Crusade. (1217-1221) Pieces of the column are also shown in chapels of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem and in the Armenian Church of the Savior in Jerusalem. Early 3rd and 4th century pilgrims like the Pilgrim of Bourdeaux and Egeria report witnessing the column of scourging in the House of Caiaphas and the Cenacle in Jerusalem.

The Crown of Thorns

In his passion Jesus was crowned with thorns. ( Matthew 27,29; Mark 15,17; John 19,2) Botanists identify ten kinds of thorny plants from Palestine as possible sources for the crown of thorns Jesus wore.

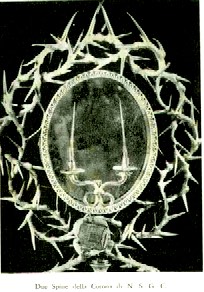

Two thorns are among the ancient relics brought by St. Helena to her palace, which later became the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Rome. They are displayed there in a reliquary.

King Louis IX of France purchased a crown of thorns during the crusades and had it enshrined at the Saint Chapelle in Paris in 1248 AD. This relic can be traced to Constantinople from the time of Justinian. (6th century) During the French Revolution the Sainte Chapelle was profaned and many of its relics lost, but the crown of thorns was removed and today is kept in the Treasury of Notre Dame cathedral in Paris. Some of its thorns were sent to other churches in Europe and elsewhere. Experts question the authenticity of this relic.

King Louis IX of France purchased a crown of thorns during the crusades and had it enshrined at the Saint Chapelle in Paris in 1248 AD. This relic can be traced to Constantinople from the time of Justinian. (6th century) During the French Revolution the Sainte Chapelle was profaned and many of its relics lost, but the crown of thorns was removed and today is kept in the Treasury of Notre Dame cathedral in Paris. Some of its thorns were sent to other churches in Europe and elsewhere. Experts question the authenticity of this relic.

The Nails

Jesus was nailed to the Cross. Three nails were taken from the 4th century excavations on Calvary by St. Helena. Tradition says she had one of the nails made into a bit for her son Constantine’s horse, another placed in his helmet to protect the emperor and his horse in battle. The other nail was placed in the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Rome.

Tradition also holds that one of the nails was given to Teodolinda, the Queen of Lombardy, who placed it a Iron Crown, kept in the cathedral of Monsa in Italy (595) and used for the crowning of the Lombard Kings and afterwards of Charlemagne and his successors. By 1600, the crown was used for 34 coronations.

Another tradition holds that a nail dating from the time of St. Helena was placed in a wooden cross that remained in Milan after the death of Theodosius ( + 395) and eventually was hung over the apse of the Milan Cathedral.

Relics of nails can be found in many of the great churches of Europe. The proliferation of these relics may be explained from the medieval practice of using shavings or fragments of the original nail and fusing it with new nails, or merely bringing them in contact with the original nail.

The Chalice of the Last Supper

Jesus took a cup at the Last Supper and gave it to his disciples to drink. “The cup of blessing we bless, is it not a participation in the blood of Christ?” St. Paul says. (1 Corinthians 10,16) Certainly the Jews would use their finest utensils for the solemn meal celebrated at Passover. Would the disciples of Jesus keep the cup he used and pass it on to later generations?

One tradition says a cup from the Last Supper was brought to Rome by John Mark, a disciple of Peter and author of a gospel. Passed on by Peter to his successors, the tradition goes on, the chalice was sent to Spain by St. Lawrence the Deacon to prevent its confiscation during the persecution of the Emperor Valerian. (253-260) Guarded by various bishops and rulers, the cup eventually was placed by King Alfonso V in the Cathedral of Valencia in Spain in 1437.

Today the cup, endangered during the French Revolution and the Spanish Civil War and placed in safe keeping at the time, is honored in a chapel of the cathedral. The history of the relic, like others, is difficult to substantiate scientifically, but the most ancient part of the cup has been dated to the 1st century and described as of Middle eastern origin.

Another tradition describes a cup from the Last Supper that Joseph of Aramethea brought to England. This tradition inspired the legends of the Holy Grail, popular in medieval times and later in our times inspiring Wagner’s opera, Parsifal and recently the film, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Reproducing the Holy Land

Over the centuries, pilgrims returning home from the Holy Land desired to build shrines and churches modeled after the pilgrim sites they visited. The Stations of the Cross in Catholic churches is an important result of the devotion of pilgrims. In Bologna, Italy, a complex of buildings, four churches and oratories constructed between the 5th and 17th centuries, recall the holy places of Palestine and the complex is appropriately called “Jerusalem.” Similarly, many churches and shrines where relics of the passion of Jesus are honored can be found throughout the Catholic and Orthodox world.

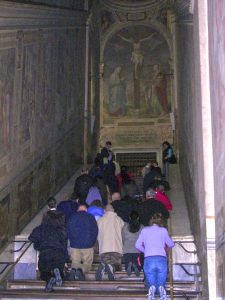

This “Holy Staircase” consists of 28 steps of Tyrian marble that legend holds were the actual staircase of Pilate’s house, which Jesus descended after being condemned.

Scala Santa, (Holy Stairs) Rome.

The Scala Santa (Holy Stairs), a prominent Christian pilgrim site honoring the passion of Jesus, is located in the complex of buildings around the Basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome and a short distance from the Basilica of the Holy Cross. The stairs, reputedly brought to Rome from Pilate’s residence in Jerusalem, lead to the Sancta Sanctorum, the personal chapel of the early Popes, where papal relics and an ancient image of Jesus Christ have been kept for centuries.

From medieval times, Christians have ascended the stairs on their knees to follow Jesus who, according to tradition, walked them to his judgment by Pilate. Christian pilgrims still do today. Pope Pius 1X entrusted the site to the Passionists in 1853.

The Scala Santa bears witness to a strong Christian devotion nourished by medieval spirituality that sought contact with places and objects connected with the passion and resurrection of Jesus. Are the stairs authentic? There is no early evidence available yet that verifies the origin of the Holy Stairs. The earliest sources describing them are from medieval times.

References:

“Relics,” The New Catholic Encyclopedia, New York, 1967

E.D. Hunt, Holy Land Pilgrimage in the Later Roman Empire AD 312-360, Oxford, 1982

Pasion de Jesucristo (Diccionarios San Pablo) Madrid, 2015